Minneapolis: Housing Miracle or Myth?

Documents coming to light through FOIA plus comments by staff show that the “Envision Evanston 2045” planning process has been steered since the bidding phase towards a “Minneapolis model” of rezoning. Proponents claim that Minneapolis has shown that upzoning and increased population density will lower housing costs. Is that true? Research suggests “not really.”

What Did Minneapolis Do?

Minneapolis lowered parking requirements and then, in 2019, eliminated single-family zoning districts, along with other upzoning, ostensibly to increase affordability through more supply. Tens of thousands of units were built, mostly through larger developments. Minneapolis’s upzoning has been called “far and away the largest densification project ever attempted in all of North America.”1 So its recurrence in City of Evanston communications, going back to before any public meeting, is no accident, but amounts to an explicit call for upzoning and density. This is significant, evidencing that a predetermined desired zoning change has shaped the Plan, rather than the normal. logical, and fair sequence of letting community-driven planning first occur.

The purpose of this writing, however, is not to dwell, for the moment, on the procedural implications of that, concerning as they are. The purpose here is to take a deeper dive into the assertion that Minneapolis's experiment "worked" and provides a template that Evanston can readily adopt with similar results. Is that so?

Context

The first thing to note that Minneapolis is very different than Evanston. It is 5 to 6 times Evanston’s size. It is the largest city in a less urbanized state. It is bordered by and considered part of the same metropolitan area with another smaller large "twin" city, St. Paul. Even so, Minneapolis even after considerable recent construction is still significantly less dense than Evanston, and began with more land per resident on which to build. Minneapolis has only 7,900 people per square mile compared with Evanston’s 9,600-10,000. In order to be “as dense as Minneapolis,” Evanston would have to lose about 15,000 residents, not add another 8,400. Conversely, Minneapolis would have to add a whopping 80,000 residents to be as dense as Evanston.

Nor does Minneapolis have a much larger city, analogous to Chicago, next to it, feeding suburban demand as upwardly mobile households seek to move in from neighborhoods like Logan Square, Ravenswood, or Lakeview. Minneapolis is more, itself, the Chicago of Minnesota -- only much less dense. Compared to Evanston, Minneapolis has less wealth, and a far lower percentage of students in its population. So it is not a good analogy and, even if its upzoning had been a roaring success, would be limited in its predictive power as to Evanston.2

Curiously, few studies compare Minneapolis with its twin, St. Paul. St. Paul's percentage of black population is similar to that of Minneapolis, but white percentage is lower, and St. Paul has a much higher percentage of Asian-Americans. St. Paul has significantly lower population density, a higher percentage of housing units that are single-family-detached, and was later to enact similar zoning changes. However, St. Paul, the less dense of the two, is the city that has lower median home prices, lower median rent prices, and, despite lower per capita income, a higher rate of home ownership.3

Also of interest is that Minneapolis, less dense than Evanston, has a slightly higher black home-ownership rate than Evanston. Density may be negatively correlated with black home ownership rates, at least with respect to single-family homes or small multi-unit buildings. Illinois towns like Olympia Fields, South Holland, Flossmoor, Matteson and Lynwood have dramatically less density than Evanston but some of the highest black home-ownership rates in the country.4

Impact on Land Values, Prices, and Rents

Drawing any hard conclusions from the Minneapolis experiment is difficult at best. Fair analyses concede this. As one nonprofit leader who studies Twin Cities housing put it, “Both Minneapolis and St. Paul have many ‘relatively experimental’ housing ordinances in place, making it difficult to disentangle the relationships between the policies, housing supply and prices.”5

One complicating factor is the degree to which Minneapolis suffered from the Great Recession. That downturn triggered a construction slowdown that contributed to demand-supply imbalance, but also, because of foreclosures, increasing vacant residential properties on city rolls to over 1,500. By 2024, that number had been reduced to 311.6 Obviously, an inventory of available cheap land facilitates building lower-priced housing, and the return of 1,200 residential lots to residency improves supply in and of itself, separate and apart from any zoning changes.

Two University of Minnesota researchers in 2020 examining impact on rents from new construction in Minneapolis, apart from zoning changes, found that new construction lowered values of higher-priced rentals close to new construction, but increased the price of lower-priced rental housing by 6.6% compared to the comparison group.7 Thus, one interpretation of the modest-at-best results in Minneapolis is that rent “reductions” were achieved by lowering the desirability of units where, previously, owners had paid a premium for the lack of density.

This finding of differing impact, facially contradictory but explained by proximity and housing type, is consistent with study of externalities of density and “empirical testing [which] finds that adjacent building height generates substantial negative externalities for surrounding building rents.”8 In plainer English, residents and buyers don’t want to be overshadowed by taller stuff next door, and so development and upzoning hurts value for close neighbors.

The first academic review specific to the Minneapolis 2018 “zoning reforms,” by planner Daniel Kuhlmann, found similar results to the Damiano-Fernier study, in that compared to similar properties in surrounding cities, the plan change was associated with a 3% and 5% increase in the price of affected housing units, with some evidence that this price increase was due to the “new development option” available to landowners. Kuhlmann, like Damiano and Fernier, found that the plan-related price increases were larger in inexpensive neighborhoods and for properties that are small relative to their immediate neighbors.9 This is similar to what experienced observers would expect in Evanston as targets for tear-downs responded to speculation.

For that reason, Kuhlmann warned of gentrification from upzoning low-density districts:

Although redeveloping single-family houses into denser 2- and 3-unit structures may do little to directly displace lower income families, if these changes alter patterns of investment and development across the city, they could contribute to larger trends in neighborhood change and, ultimately, displacement of people with low incomes from the city.

“ ….[T]here has been little empirical research on how zoning reforms affect neighborhood change and investment. This is an important question, particularly because some of the most trenchant opposition to upzoning concerns the potential of such changes to lead to displacement of people with low incomes.10

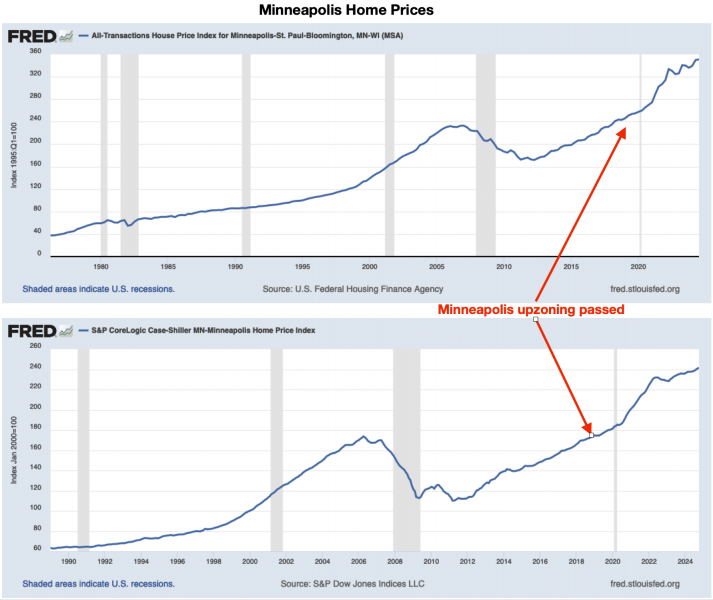

A more recent 2024 eview of the literature analyzing the Minneapolis experiment found that housing gains were “modest” at best.11 Census data seems to bear that out. The 2022 census estimate was that median rent in Minneapolis was $1,267. The estimate in July 2023 was $1,328, a one-year increase of 4.8%. Minneapolis news accounts also confirm that after the upzoning, home prices have overall continued to rise.12 That fact is confirmed by studies,13 as shown here:

Even advocates of upzoning/deregulation concede that the results have been nuanced and complicated. For one thing, in 2018, the year before the single-family zoning elimination, “Minneapolis approved a record-breaking 4800 dwelling units, compared to an average of 3000 in the three years prior, and around 3400 in the three years since.”14 The author of that finding, an Australian upzoning advocate and blogger, cautioned that the Minneapolis results were not necessarily transferable to other jurisdictions, saying “single-family zoning abolition may not be the sole solution for increasing housing supply in areas where multi-unit developments and apartment construction are already prevalent.”15 Evanston is such a place.

Another confound is the overall economy. Interest rates near zero during the pandemic made it easier to build. As interest rates started to rise to combat inflation, and as demand on supply chain dramatically increased costs, and other inflationary impacts rippled across the economy, building (or maintaining) any kind of housing, let alone new affordable housing, became more difficult. Most of the affordable housing added to the Twin Cities since the Minneapolis upzoning has been created through preservation, not new construction, and in 2022 and 2023, as costs caught up (and as some inventory was flipped), the rate of total affordable housing produced annually in the Twin Cities has fallen off significantly.16

Multiple commenters also point out that Minneapolis population has actually declined in the past few years, which would tend to skew the market. That can’t be attributed solely or even primarily to the zoning changes, because the civil unrest in Minneapolis after the death of George Floyd may have been a contributing factor to residents leaving the city. It’s possible that the upzoning was a contributing factor to exodus, because it was highly contested (see Controversy, below at p. 5) and may have soured some residents on living there. Regardless of cause, however, the Census Bureau in 2022 agrees with critics of the Maltman article, estimating that between July 2020 and July 2022 Minneapolis lost almost 5,000 residents; as of July 2023 that number was almost unchanged.17

Controversy and Litigation

The Minneapolis upzoning plan was opposed by activists of color, environmental groups, and smart growth advocates. The smart growth advocates labeled it “irresponsible planning.”18 Nekima Levy Armstrong, a black activist, said “Residents of color already face significant barriers to home ownership, which would have been exacerbated under the plan as a result of reduced access to and availability of single family properties.”19 Environmental criticism was that “by deregulating development, it puts the environment directly at risk through cumulative harm” from density-related impacts, a conclusion bolstered by an Initial Environmental Analysis conducted by an environmental engineering firm.20

The coalition opposed to the plan sued. The trial court agreed with them, finding that the plan conflicted with environmental goals, holding, “Increased population density is an affirmative feature of the residential portions of the 2040 Plan, a feature that has not been present in any previous comprehensive plan.” The ruling was hailed by environmentalists.21 The injunction by the trial court was reversed by an appellate court in May, 2024, not on its merits, but because of limits on the trial court’s power.22 However, it should be noted, the litigation continued for years after the plan’s adoption.

Conclusion

It would be a planning mistake to draw hard conclusions as to ultimate impact of Minneapolis upzoning on affordability, let alone to assume that it represents a good template for Evanston.

In Minneapolis, the many more units built produced gains in housing supply affordability that are modest at best and whose stickiness is not certain. Rents and home prices continue to rise. The confounds of pre-existing housing vacancies, pre-existing incremental measures, and population loss in Minneapolis over the last four years prevent any conclusive finding as to even those modest benefits, or environmental costs. Explanation of why less dense, more single-family-oriented St. Paul was (and remains) more affordable is lacking, and those facts undermine the upzoing thesis. The applicability of a scheme in Minnesota’s largest city to an already denser and more affluent inner-ring Chicago suburb like Evanston has inherent questions.

Even if the modest alleged benefits are possibly replicable, weighing against those are the likelihood of gentrification and displacement suggested by research and common sense, with “affordability” gains occurring primarily as some more desirable residences become less so due to crowding. Evanston is expensive because it is desirable. Increasing affordability by reducing desirability and home value, whether in relatively scattered instances impacting surprised individual property owners, or on entire blocks or in existing multi-unit buildings, is something no Evanstonians have asked for, and would be contrary to stated goals of all other planning Evanston has ever done. A commitment to environmental sustainability also requires taking the environmental objections to upzoning raised by the groups in Minneapolis seriously.

Given that the Minneapolis experiment in upzoning and densification yields no firm evidence of a successful model that can be applied to Evanston, the greatest significance of its recurring reference in Envision Evanston 2045 discussion is to suggest that the “solution” was determined before the planning. If so, the planning process has largely been cover to achieve the rezoning desired by certain interests, which is a major procedural problem, requiring remedy. -- JPS

Notes

1 Smart Growth Minneapolis, “The Problem,” https://smartgrowthminneapolis.org/our-work/problem/

2 Minneapolis does not plan to do that, it projects that it still needs to add housing for its existing population. But note, mathematically, any city that is adding population at the same time that it is building housing is making it more difficult to reach its goals. The target moves. That is one reason why it is difficult to build one’s way to sustainability or affordability.

3 “Minneapolis, MN vs St. Paul, MN,” https://www.city-data.com/compare/Minneapolis-MN-vs-St_-Paul-MN

4 Ted Slowik, “South suburbs contain 5 communities with nation’s top black homeownership rates,” Daily Southtown (Dec. 13, 2018), https://www.chicagotribune.com/2018/08/26/south-suburbs-contain-5-commun...

5 Madison McVan, “Twin Cities met new housing targets in recent years, but growth slowed in 2023,” Minnesota Reformer (Jan. 16, 2024), https://minnesotareformer.com/2024/01/16/twin-cities-met-new-housing-tar... (quoting Dan Hylton of HousingLink).

6 Elliot Hughes, “Vacant Since the ‘90s? Minneapolis pushes to reduce number of long-empty buildings,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune (July 18, 2024), https://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-proposal-would-mandate-annual-fi...

7 Anthony Damiano and Chris Frenier, “Build Baby Build?: Housing Submarkets and the Effects of New Construction on Existing Rents,” Ctr. for Urban and Reg’l Affairs (Oct. 16, 2020), https://www.tonydamiano.com/project/new-con/bbb-wp.pdf. Note CURA has an earlier draft online.

8 Chuanhao Lin, “Do households value lower density: Theory, evidence, and implications from Washington, DC,” 108 Regional Sci. & Urban Econ. (2024), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2024.104023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166046224000474. Lin found that the data suggested that externality costs depend on both height and building separation of adjacent buildings.

9 Daniel Kuhlmann, “Upzoning and Single-Family Housing Prices: A (Very) Early Analysis of the Minneapolis 2040 Plan,” 87 J. Am. Planning Ass’n 383-395 (online: 16 Feb 2021), https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1852101

10 Kuhlmann, id., at n.5.

11 April Towery, “Minneapolis Abolished Single-Family Zoning But is That The Answer to More Affordable Housing?” https://candysdirt.com/2024/01/01/minneapolis-abolished-single-family-zo... (Quoting Governing.com journalist Jake Blumgart, at https://www.governing.com/jakeblumgart).

12 Greta Kaul, “Why home prices in the Twin Cities keep going up,” MinnPost (Apr. 7, 2022), https://www.minnpost.com/economy/2022/04/why-home-prices-in-the-twin-cit...

13 “All-Transactions House Price Index for Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI (MSA),” Fed. Res. Bk. of St. Louis (Nov. 26, 2024), https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ATNHPIUS33460Q; “S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller MN-Minneapolis Home Price Index,” Fed. Res. Bk. of St. Louis (Oct. 2024), https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MNXRSA#. Graphs are shown above.

14 Matthew Maltman, “A Detailed Look at the Outcomes of Minneapolis’ Housing Reforms,” One Final Effort.com (Apr. 17, 2023), https://onefinaleffort.com/blog/a-detailed-look-at-minneapolis-housing-s....

15 Id. (emphasis supplied)

16 Housing Link, “Housing Counts,” https://www.housinglink.org/Research/Counts; see also “Twin Cities met new housing targets in recent years, but growth slowed in 2023,” supra n.5.

17 U.S. Census Bureau, QuickFacts | Minneapolis city, Minnesota,

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/minneapoliscityminnesota. The 2024 results have not been published. A .pdf of the 2022 estimates no longer appears at the foregoing link is available on request.

18 Smart Growth, supra n.1.

19 Susan Du, “Minneapolis cannot proceed with 2040 Plan, court rules,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune (Sept. 5, 2023), https://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-cannot-proceed-with-2040-plan-co...

20 Smart Growth, supra n.1. See generally Kirsten Pauly, et al., Sunde Engineering, “Environmental Analysis: Minneapolis 2040 Plan” (Nov. 2018), https://smartgrowthminneapolis.org/wp-content/uploads/Sunde-Environmenta.... The review found that environmental impacts on residents would include increased noise impacts, increased pedestrian traffic, increased vehicle traffic, increased vehicle congestion and idling, decreased air quality, increased parking constraints, negative impacts to existing viewsheds (landmark buildings, open spaces, water

bodies), longer hours of activity, reductions in privacy, increased light and glare from buildings, greater impacts from construction if construction of larger buildings than previously permitted increases the duration of construction activity, decreased access to light for surrounding properties, shadowing of adjacent properties; and impacts to existing solar panels on neighboring structures. Id. at 10-11.

21 Kevin Reuther, “Op-ed: Court got it right on 2040 plan: Minnesota Environmental Rights Act provides essential protection,” Minn. Reformer, (Feb. 10, 2023) https://minnesotareformer.com/2023/02/10/court-got-it-right-on-2040-plan....

22 Christopher Ingraham, “Minneapolis 2040 plan can once again go forward, appeals court rules,” Minn. Reformer (May 13, 2024), https://minnesotareformer.com/briefs/minneapolis-2040-plan-can-once-agai...

- Printer-friendly version

- Log in to post comments