More Buildings in Evanston = More Cars

Since 2015, Evanston basked in the sobriquet “the suburb that killed the car,” promoting an image of an imminent car-free utopia. From environmental nonprofits to editorial pages, we heard that Evanstonians were making different “transportation choices” warranting overhauling our zoning. By summer 2023, City Council was mulling wholesale reduction of parking requirements for new developments in an expanded radius, up to 1/2 mile, from train stations, or even putting a cap on allowed parking, to force those “choices.” The theory: development and greater density in transit-rich Evanston would spark abandonment of vehicle ownership. This has been a refrain in current citywide planning ongoing. Yet data specific to Evanston supporting those policy assumptions was scant to nonexistent. Now, information obtained through FOIA provides some answers.

Fully cleaning up, sorting, and analyzing what amounts to over half a million data points is still ongoing. But because of the current headlong rush to both re-plan and re-zone simultaneously, Evanston residents should know the broad brush: Evanston’s growing density of housing is associated with an increase, not decrease, in passenger vehicle ownership. Planned developments contribute significantly to that increase, and greater density is not, overall, spurring a significant move away from personal vehicles as preferred transportation choice.

FINDINGS

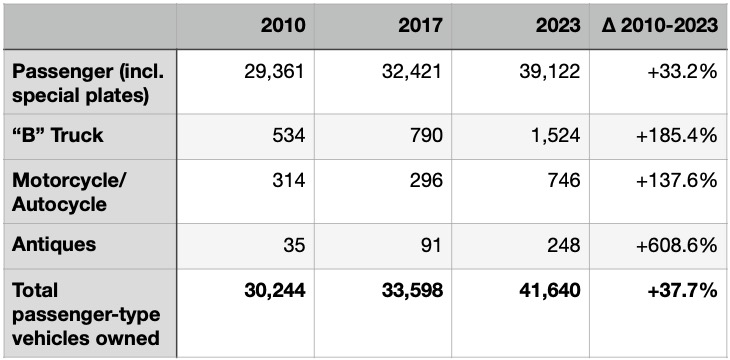

1. Evanston did not “kill the car.” Quite the opposite. Evanston since 2010 has seen a dramatic increase in the number of passenger vehicles registered here, and this increase parallels strongly with the building boom that has added thousands of units and thousands of additional population to Evanston. The following are sufficient to show the trend:

According to data Evanston produced, the town currently has more passenger motor vehicles than in a decade, and possibly more than ever. A temporary disposal of personal vehicles out of economic hardship after the 2007-2009 economic crisis, from which recovery took years, was misinterpreted by some as a change in transportation choices and modes. However, a return to relative economic stability by the mid-2010s restored the previous status. The car is alive and well in Evanston and, if anything, the recent pandemic, lockdown, and related effects created additional demand that offset financial hardship.

2. Evanston’s passenger “fleet” is getting bulkier and more expensive. While there has been small growth in EVs and motorcycle-type vehicles, the overall trend in Evanston, as in the US generally, has been towards vehicles that are bigger, more energy-intensive to manufacture and operate, and more expensive. Over a little more than a decade, Evanston saw an increase of almost 1,500 hybrids and electric vehicles, but that was dwarfed by the increase of nearly 10,000 conventional-engine vehicles and SUVs. Note the tripling, in the table above, in number of “B” “trucks,” which includes some bigger SUVs as well as pickups and vans.

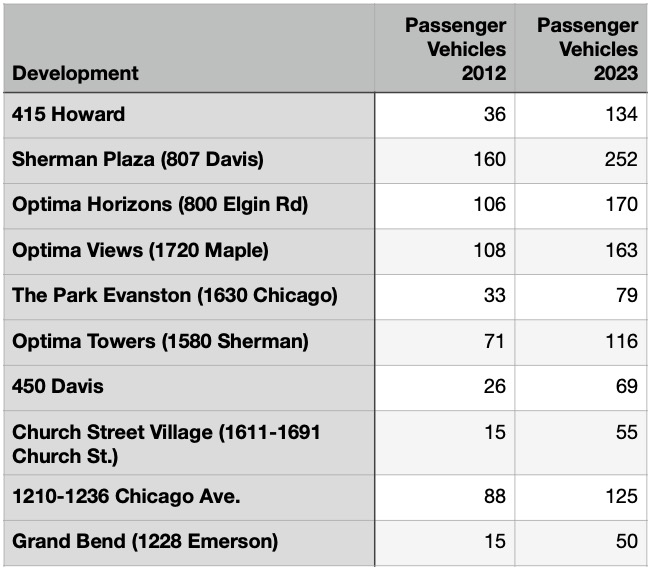

3. Multi-unit development drives vehicle ownership. A large driver of Evanston’s motor vehicle growth, if not the single greatest driver, has been the construction of multi-unit housing developments. The greatest number of vehicles per block in Evanston is found on streets with the greatest density of housing units. More density is leading to more vehicles even if a greater proportion of smaller units (studios and 1BRs) is causing marginal reduction in vehicles per household.

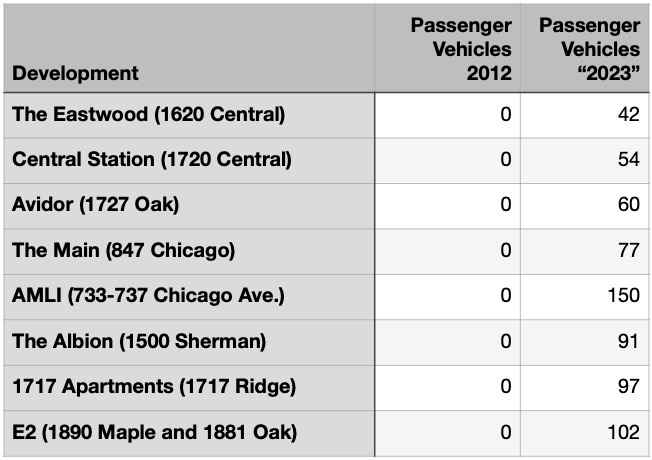

A handful of examples of transit-proximate developments that came online over one decade illustrate this:

4. “Car-less choices” do not last. Newer developments such as the above often first show garage space not used to capacity. Utilization also fluctuates during events like a recession or a pandemic. However, the trend over time is that the number of vehicles registered to multi-unit developments tends to increase, as shown in the examples below:

This trend makes sense upon reflection. A new development may initially show low vehicle ownership for numerous reasons. If homebuyers purchase up to the limit of their cash flow, that may inhibit vehicle purchases or leases. Many renters, especially if moving from elsewhere into more expensive units in Evanston, may face similar constraints. Also, residents may simply plan to get by as a zero-car or one-car household.

Over time, however, needs, finances, and choices evolve. A resident may lose a job in the Loop to which they commuted by CTA, and their next job is in Mundelein. Or a couple’s schedule gets busier, due to children, greater community involvement, medical appointments, or aging parents. Having a ready-clinic within walking distance doesn’t matter if the specialist you see is at Glenbrook Hospital. No one is going to Über to a child's hockey tournament in Kenosha. For countless reasons, residents may over time just find it not as practical as they imagined to have as few vehicles as they initially had at move-in.

Additionally, development stats may undercount because a car that is parked in or near a new building (i.e. on the street) may for some time lag and continue to be registered at a non-Evanston address: a student's car may be registered to parents in Arlington Heights or Wisconsin; a new resident may not immediately notify the Secretary of State of her address change, and send in payment from forwarded mail for a cycle or two.

The explanations are theoretical, but the trend is real.

5. Census estimates back up the registration location findings. As a check on my own research, I consulted some federal stats. In 2007, the Census Bureau estimated that 23,483 Evanston households owned a collective minimum of 35,193 vehicles. That figure dropped in the economic crisis, then rebounded. Fifteen years later, the most recent Census Bureau estimate, for 2022, was 25,852 households owning a collective 38,526 vehicles. So, per these estimates, Evanston added 2,300 households -- and at the same time added 3,300 vehicles. This accords with the growth shown by the vehicle registrations data. Interestingly, the Bureau estimated that in 15 years Evanston had gained 1,500 more households without cars. However, it estimated the growth in vehicle-owning households as twice that. Since the number of single-family houses changed immaterially in that timespan, the main growth had to come from additional multi-unit housing. Also interesting was that the Census Bureau found that the most common form of commuting among Evanston residents is driving to work, alone.

6. Parking-constrained developments still result in vehicle ownership. At least two developments in recent years aspired to enforce a less vehicle-oriented life. “The Link” (811 Emerson) received dispensation for lower parking requirements than typical, as did 1590 Elmwood, now known as “The Scholar,” which was originally developed (and covered in the press) with a Maple Ave. address. The latter boasted only 12 parking spaces; as of 2022 there were at least 19 vehicles registered to it, and The Link had 33. Because there has been insufficient time for the “evolution” effect to occur, especially during the pandemic which disrupted much normal behavior, it is hard to draw hard conclusions. Whether the lower vehicle ownership is a function of disincentives working, or simply appealing to those who didn't have vehicles anyway, it is notable that “The Scholar” building was sold and now affirmatively markets toward students. Possibly, a limited number of such developments oriented toward students may feasibly result in reduced-vehicle occupancies, as might also some senior housing. However, the mass of contrary data counsels against assuming that those results are scalable or can be extrapolated to the typical Evanston family or household, present or future.

SUMMARY AND POLICY RAMIFICATIONS

The increase in Evanston housing units and density, and in particular dense multi-unit housing, can not be said to be “getting people out of cars” to any great degree. The bulk of Evanston residents who live where trains are not within easily walkable distance are certainly not giving up vehicles. Near transit, the number of vehicles per household appears to be lower, but that statistic is associated with (and confounded by) smaller household size in smaller units, and demographics (few high-rise units, for example, have two working parents and more than one driving-age high-schooler or young adult, as do many houses). There is some slight evidence that building a development specifically for the niche market of well-to-do young people without cars, graduate students, and foreign students, can have limited success; however, those projects are atypical, and assuming scalability lacks foundation.

Thus the promotion of greater residential density and in particular the elimination of parking requirements or forbidding ample parking based on a hypothetical change in “transportation choices” or supposed reduction in carbon footprint is very flawed. Multi-unit residential housing development has increased Evanston’s vehicle fleet by, conservatively, thousands of vehicles, and has increased its transportation-related carbon footprint. More of the same is likely to produce more of the same.

No question, some choose not to have a personal vehicle, and that works for some lifestyles. Evanston should continue to enable and support active transportation as well as transit use. However, that is not practical or the choice for most. On the contrary, it’s pretty clear that more units = more vehicles. It's also important not to critique the residents of those buildings when opposition is to the development decisions themselves. No one can be faulted for wanting to live in Evanston, and we welcome all neighbors who contribute to the community.

However, capacity matters. More congestion translates to actual cost to all residents, old and new, in terms of time spent looking for a parking space, walking to or from a vehicle that is parked, and being stuck in traffic. Congestion and/or lack of street parking may also discourage non-Evanstonians from visiting, or patronizing Evanston businesses.

The policy push toward forcing Evanstonians to accept greater density and growth rests on three legs: sustainability, affordability, and equity. This examination of one leg, sustainability, shows that reducing transportation carbon footprint through construction and density is not borne out by evidence.

-- Jeff Smith

- Log in to post comments